Fifteen or so years ago, Michael Gilvarry and his team had a eureka moment.

Gilvarry, now Head of R&D, Neurovascular and General Manager at Johnson & Johnson MedTech, was working on devices for thrombectomy, at the time a relatively new treatment for stroke in which blood clots are mechanically removed with the use of fine catheters, clot-capturing devices and suction. As thrombectomy became an increasingly important treatment, medtech companies raced to develop products to help physicians perform the lifesaving procedure.

But there was a problem with how those device-makers were approaching the task, Gilvarry realized. And the problem was fundamental.

From Gilvarry’s point of view, many were designing their thrombectomy portfolio without a sophisticated, thorough understanding of the physical makeup of the blood clots that those products were intended to remove.

“We were designing devices without knowing what the clots were composed of,” Gilvarry says. The prevailing thought at the time was that a clot was a clot; all were essentially the same.

But as thrombectomy became more widely used—and physicians began seeing the clots they were removing up close—they realized that wasn’t the case at all. Blockages that caused stroke were anything but uniform. Newer blood clots, scientists observed, were bright red and gel-like. But more mature clots could be harder or more fibrous, and often lighter in color. They could also take various shapes—sometimes globular, sometimes long and stringlike. Calcified, stiff clots and clots resistant to pulling, for example, could present special challenges for physicians during thrombectomy.

Researchers began to realize they needed to prioritize the study of stroke-causing clots before they could design and produce the best possible products for their removal. “We’d been putting the design before the science,” Gilvarry says. “We needed to put the science first.”

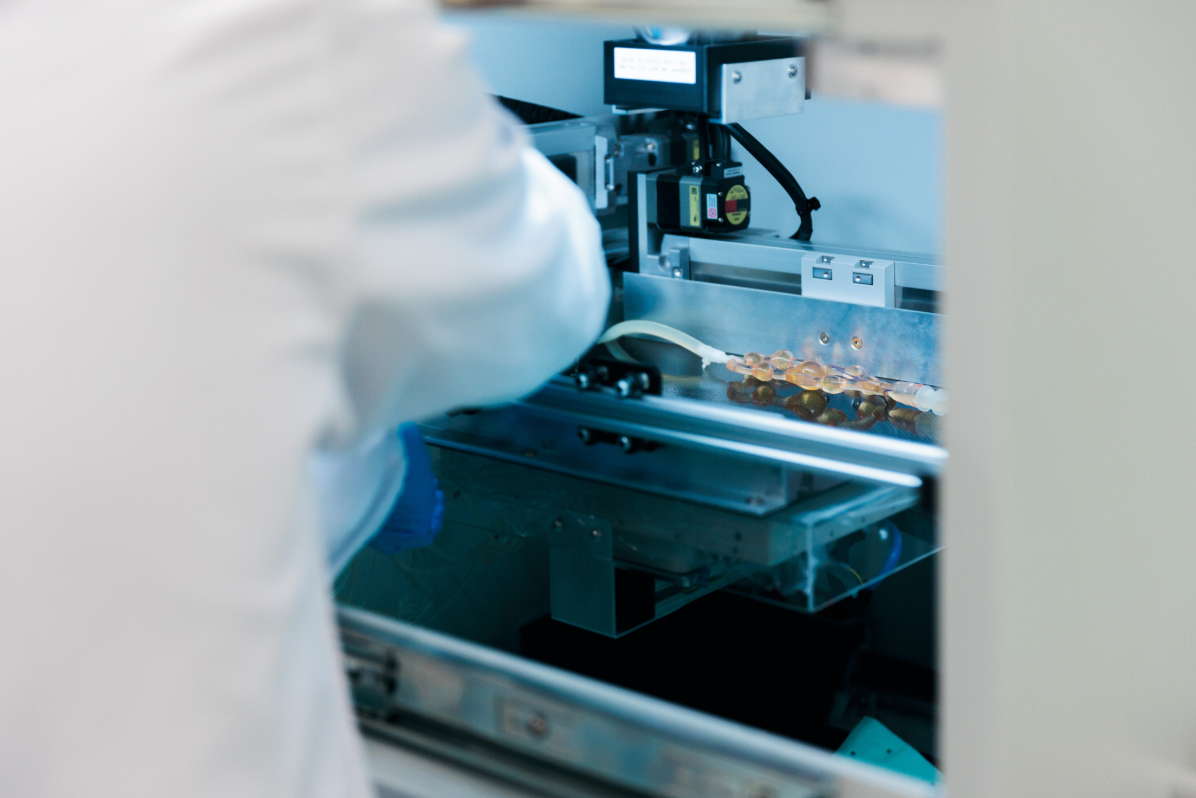

Work underway at NTI in Galway, Ireland

Unique research for an urgent cause

That’s partly why, in 2014, Johnson & Johnson MedTech launched NTI, its scientific research arm, led by an interdisciplinary team of scientists and engineers that work in collaboration with researchers and clinicians in and outside of Johnson & Johnson.

Located at a state-of-the-art research facility in Galway, Ireland, “we sit at the intersection of clinical research, academic research and our own internal research and development team,” says Ray McCarthy, R&D Director, NTI Research Lead, Johnson & Johnson MedTech. “Our job is to translate clinical patient needs and academic research into something our development team can innovate around.”

One of the NTI’s founding, flagship endeavors has been to study the very problem Gilvarry was interested in—blood clots, the cause of stroke—as never before. At the facility, Gilvarry, McCarthy and their colleagues are collaborating with physicians from across the world to collect clots retrieved from patients in a clinical setting during thrombectomy so that they can be banked and systematically analyzed by Johnson & Johnson and other scientists.

Learning about the complex nature of blood clots unlocked new research pathways for the NTI team. As their understanding developed, NTI scientists figured out how to produce clots that mimicked real ones. Those clot replicas could then be used in simulations of real-life stroke scenarios, which engineers could employ to gain insights into how well their device prototypes were working and how to refine and improve them.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about the disease, and we're learning as we go,” says Gilvarry. “I think what sets the NTI apart is the approach that we take to understanding the science of these problems before we develop devices for treating them.”

Recognizing the innovative work of the NTI, J&J MedTech deepened its support for the Galway group, announcing in 2022 a €50 million investment into neurovascular R&D. And the research underway is critical because, globally, stroke is the second leading cause of death, and one in four people above age 25 will experience one in their lifetime.

Since 2022, McCarthy says, that investment has been used to attract the brightest minds in the field, advance the facility’s prototype manufacturing capabilities and broaden the NTI’s research focus to include other neurovascular diseases.

“We’re at the tip of the iceberg in terms of what we can do”

One such challenge is chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH), a potentially life-threatening condition in which blood slowly collects under the skull on the brain’s surface. It often follows a head injury, with symptomatic patients having a very poor prognosis by two years after first identification.

In mild cases, cSDH can be monitored without intervention; the body can reabsorb the blood, effectively resolving the problem. But hematomas that put dangerous pressure on the brain must be addressed, and quickly.

In recent years, scientists on the NTI team have been working on a new method of treating cSDH using a gluelike agent known as a liquid embolic, which can block the minor blood vessels that feed a hematoma and stop its progression.

In the United States, the liquid embolic has been a safe and effective therapy in the treatment of arteriovenous malformation (AVM), an abnormal twisting of blood vessels in the brain that can interfere with normal blood flow. Certain AVM cases are treated with surgery, and in such cases, a physician may administer the treatment ahead of the procedure to control blood flow to the surgical site.

Now, NTI researchers are evaluating its use for chronic SDH, a newer application for the liquid embolic.

Among its benefits are that it’s fast-acting and easy to use. When injected into a superficial blood vessel that feeds a cSDH, the liquid embolic halts the flow of blood, rerouting it elsewhere in the brain. The hematoma then naturally shrinks, resolving a patient’s symptoms and disappearing over time. “It’s very straightforward and simple to use,” says Emmanouil Kasotakis, Ph.D, Principal Polymer Chemist at Johnson & Johnson MedTech, “and importantly, it has a strong safety record and efficacy across approved indications.”

In its present formulation, the solution must be mixed by a physician before administration. Kasotakis and his team are currently working on modeling real-world, anatomically correct models to understand how the liquid embolic is delivered to the middle meningeal artery (MMA).

The team’s contributions are giving physicians more and better tools to help patients with cSDH, Gilvarry says.

“Treating cSDH with liquid embolics is a newer area of research,” says Gilvarry. “We’re approaching it as we do all of our research: by understanding the anatomy of the microcirculation within the brain, replicating that in simulation models and testing variables within those simulations.”

Going forward, the NTI team plans to leverage the same approach to investigate a host of other neurovascular conditions, which may include hydrocephalus, a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid on the brain, and aneurysm, which occurs when a blood vessel in the brain bursts.

“We’re at the tip of the iceberg in terms of what we can do with our capabilities," McCarthy says.

Johnson & Johnson’s emphasis on building strong relationships with clinical research partners makes the work all the more rewarding, he adds. “We’re all engineers and scientists who got into this work because we’re interested in solving problems, just like physicians,” McCarthy says. “We all want to come up with better ways of treating patients.”

US_NEU_ALLN_409116

© Johnson & Johnson and its affiliates 2025