The leading cause of death in the United States? Heart disease, and coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common subtype. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 20 adults age 20 and older have CAD (about 5% of the total population). And gender gaps exist at every level of this disease, from diagnosis to treatments, resulting in worse outcomes for women.

The first of its kind, Johnson & Johnson MedTech’s female-only study of coronary interventions in complex calcific disease is seeking to confirm benefits of Shockwave intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) in women.

The co-principal investigator of the EMPOWER CAD study, Alexandra Lansky, M.D., a professor in cardiovascular medicine and Director of the Heart and Vascular Clinical Research Program at Yale University School of Medicine (pictured at right), discusses common misconceptions around women with CAD, the gender gap in treatment and study leadership, and the importance of equitable research for both patients and healthcare providers.

Q: Why have CAD treatments typically resulted in worse outcomes for female patients than for males?

A: That’s actually a bit of a misconception. It's not that all women do worse with coronary disease treatments. In fact, for the vast majority of women, if they get proper treatment, the outcomes are just as good as men. But there are key differences that cause this reported gender gap.

The first is that women tend to present with coronary disease 5 to 10 years later than men. Because they’re generally older when they present with CAD, women typically have more risk factors associated with age, such as diabetes, hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. But if you adjust for these risks, you find that outcomes are actually just as good.

Additionally—for multiple reasons—women don't get access to equal or as aggressive treatment as men do. If women get the same treatment as men, the outcomes are as good as our male counterparts.

However, there are also some cases, such as STEMI (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction), where even adjusted for the previously mentioned risk factors, women still do worse than male patients. And that might be because some of the symptoms are different in women than in men, which leads to delays in treatment. Additionally, the blood vessels in women tend to tear, dissect and perforate more. So when we treat women with calcified lesions with traditional atherectomy devices, the vessels seem to be more fragile than in men.

Q: What are “silent symptoms” and how to do they contribute to the amount of women who are diagnosed with CAD?

A: That's really a key issue that we need to better understand. In the context of a heart attack, about 15 to 20% of women don't have typical symptoms. They don't have chest pain or angina. And there are very few studies that have looked at the impact of asymptomatic coronary disease, which is not necessarily specific to women.

In the few studies that have looked at this, if you look at that cohort of patients and you track their outcomes long term, they don't do well. They have higher mortality, higher myocardial infarction rates and higher need for reintervention. So we need to study this more in order to better understand it.

For whatever reason, these patients do not have the symptoms and warning signs of coronary disease that otherwise would alert people to go to the emergency room. And that explains why their outcomes are much worse. It's something that we have not studied well in women cohorts. And we absolutely need to do that, because clearly there are more women that are asymptomatic than male patients. And that may be another factor that contributes to some of the worse outcomes we've seen in female patients.

The primary objective of the study is to amplify the evidence in women. Another important objective is to empower our female clinicians. Only around 5% of interventional cardiologists in the U.S. are female. And when you look at most studies outside of this one, very few women participate in study leadership.

Q: How is coronary intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) different from historic treatments?

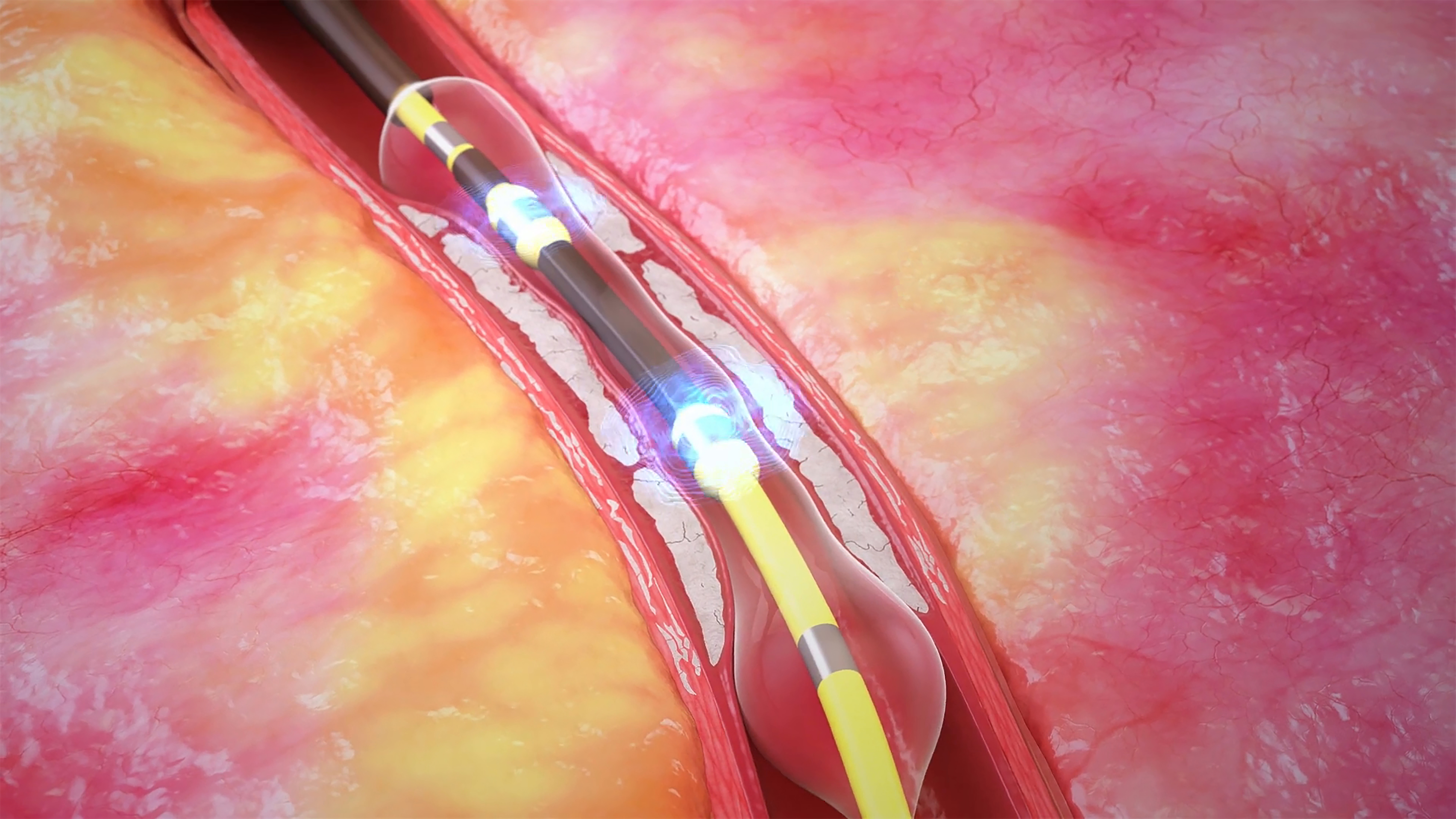

A: The standard treatment is with angioplasty done minimally invasively, and using a stent implantation. Drug-coated stents give the best long-term outcomes in general. IVL (pictured below) is specifically for people with calcium in their lesions in the stenosis in the areas that get treated. To get the best results with the stents, we need to be able to expand the stent so it hugs the wall of the blood vessel. When there’s calcium, you cannot expand the stent and it can trigger thrombus formation. Stent thrombosis and restenosis are some of the worst things that can happen to a patient.

The genius of IVL technology is that it is balloon-based versus a traditional rotating or orbital atherectomy devices that uses a rotating burr or crown to cut or scrape away calcified plaque. Through a delivery of sonic waves, IVL fractures the calcium inside the vessel wall and changes the compliance of the blood vessel. So when you go in with your stent afterwards, you can expand the stent and you get the best acute results, which translates into the best long-term results.

Q: How does this trial add value to the field?

A: This study is very bold. There are few studies that are specifically in women. We're trying to narrow the gap and catch up to fill in the evidence that is needed to better understand what the outcomes are in female patients. In our study, 400 patients with calcified lesions are going to be treated with an IVL-first strategy to understand the acute results. We will also be tracking these patients for three years to understand the long-term results. With that data, we’re going to understand how often IVL is successful, how good the strategy is at expanding the stent in women and the complication rates both immediately and in the long term.

Another exciting thing about this study is our substudy of optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging, which will allow us to really understand the incremental improvement with IVL and the stent measurements at the end of the procedure. This portion of the study will be reviewed independently and will be the largest of its kind.

Q: Why have women historically been left out of clinical trials in heart disease?

A: There are a lot of different reasons. In terms of patients, I think women are inherently a bit more skeptical, and may be reluctant to engage in clinical studies.

Women's decision-making processes can be very different from men's. From surveys, we’ve found that women like to have more time to digest the information and analyze the risks of a clinical trial through conversations with family and friends. And rarely do we as investigators give women enough time to make this decision. Men tend to make decisions faster in this sense. Part of that has to do with the fact that women are generally the primary caretakers. Women are likely to be so central to everyone around them—husbands, young children, adult children, pets, etc.—so it’s an issue of how much time they think these clinical trials will take away from those responsibilities.

As researchers, we need to put more effort into accommodating for these factors and including women who have caretaking responsibilities or who are at childbearing age in clinical trials. There are mechanisms, such as telehealth or going to a patient’s home to do follow-ups, that can address these barriers and make trials more inclusive. But right now we don’t implement them often enough.

There are some real disparities in access to care between male and female patients. And in cardiogenic shock, those disparities are even worse, resulting in 60% mortality rates for women. To address that, we’re working on a follow-up from the consensus we wrote that will identify areas that we need to study, specifically in women, to build the evidence we need to identify the best treatments for women.

Q: What does this trial mean for making future clinical trials more equitable?

A: It's tackling multiple things. The primary objective of the study is to amplify the evidence in women. Another important objective is to empower our female clinicians. Only around 5% of interventional cardiologists in the U.S. are female. And when you look at most studies outside of this one, very few women participate in study leadership. The reasoning behind that is threefold: They’re simply outnumbered by male clinicians in the field, they might say they just don’t have the exposure training, or they might not have been invited to lead a study like this. We hope that by offering study leadership roles in EMPOWER CAD to female physicians, it gives them those things, which will empower them to take on more leadership roles in studies in the future.

We have pushed to identify and engage female clinicians, and more than 71% of enrolling sites are led by women. And I'm very pleased to report the enrollment in the study is ahead of our timelines, which is unheard of. I think that is very potent evidence to show that when we do make the study about women, they are more likely to participate.

Q: What is your advice for providing unique opportunities for women to lead studies?

A: My advice is that you have to be persistent. I’ve been in this field for a few decades and you do get knocked down. But everybody gets knocked down, not just women. You have to pull yourself back up. There are going to be obstacles, but if you let the obstacles prevent you from reaching your goals, you’re not going to get very far.

And you have to create the interest in what you want to study. We didn’t ask to do this study out of the blue. We went through the due diligence to show the need that convinced our partners to support this study. You have to create the engagement and the reason for proceeding.

Q: What do you envision as next steps in working toward inclusion in the field, in both treatments and in clinical studies?

A: This study is a great case model for what we need to do in the future. It came about because we were working on a consensus document, we identified the gap, and then we proposed this study to address that gap and we had a very positive response from our sponsor. And now we hope to present primary endpoint results this year.

Additionally, there are some surgical trials specifically in women being run currently. That's a huge step in the right direction. We need to understand what is the best treatment from a surgical standpoint for female patients.

There are some real disparities in access to care between male and female patients. And in cardiogenic shock, those disparities are even worse, resulting in 60% mortality rates for women. To address that, we’re working on a follow-up from the consensus we wrote that will identify areas we need to study, specifically in women, to build the evidence we need to identify the best treatments for women.

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)